RE:SEARCH

In an earlier post regarding CRS, Bill Caudill and his TIB's, I mentioned CRS's commitment to research, and that I'd be returning to his "Things I Believe" and their relationship to current architectural issues. Flipping through the book, I came across the following TIB on research from Bill in April 1966.

"There are a lot of definitions for research.

I like this one:

'Regarding the search for truth'

It even looks good:

RE:SEARCH"

A few weeks ago I came across some new information on CRS. In her excellent paper, Marketing through research: William

Caudill and Caudill, Rowlett, Scott (CRS), Avigail Sachs provides historical analysis of the "research attitude" of the firm in its formative stage. She notes their power to integrate professional practice and research, in both marketing and design, while leading the AIA and profession in applying research and new techniques to the design world. In her conclusions, she advises contemporary architectural practices to learn from CRS's early stage commitments to research, scholarship, marketing and design leadership. Though many contemporary A/E firms have benefitted by engaging research in their practice methods, the profession still has a long way to go to bridge the research/practice gap.

For example, a few months ago I prepared a short paper in our firm, advancing the argument that architectural programming is actually primary research. The word research often has multiple meanings and requires a variety of skills that many architects and engineers are not trained to perform. Most design professionals understand that primary research is the collection and evaluation of data leading to knowledge that does not already exist, but what isn't clear to practicing professionals, is the linkages between architectural practice and design research. Looking at our profession and our firm's design practices, one might raise the question, what parts of our current methods are or could be defined as research and how as a firm and profession can we better understand and refine these methods.

In his book, Inquiry by Design, John Zeisel sets out some basic concepts regarding the relationship and cooperation between research and design, from the perspective of an environmental behavioral researcher and a designer. He argues that designers and researchers can work together to solve more broadly defined design problems than they could each solve alone. A major issue, however, is the usefulness of research material. It must be in a form that designers can not only use, but in turn, improves the chance that research information can be tested in practice. Research investigators learn by making hypothetical predictions, testing ideas, evaluating outcomes and modifying hypotheses. These activities are the basis of their collaboration and cooperation.

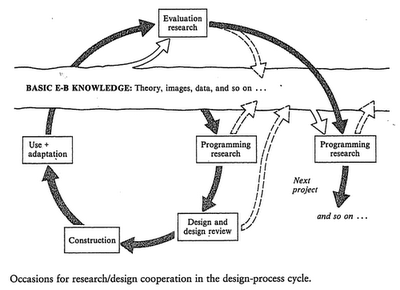

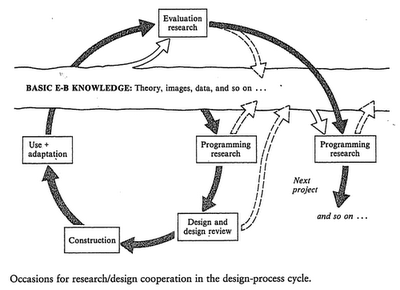

Zeisel states that there are at least three day to day design practices that offer opportunity for research/design cooperation.

1. Design Programming: research for the design of a particular project

2. Design Review: design assessment for conformance with exis

ting environmental behavioral research knowledge

3. Post Occupancy Evaluation: assessment of built projects in use in comparison with original design goals/hypotheses

This diagram is from Zeisel's text and describes the relationship between environmental behavior knowledge and the design process.

Of these three project practices, a revised approach to programming offers a major opportunity to recognize its research nature, improve our methodology, and create a basis for innovation and idea generation. In some ways over the past forty years, programming has moved from a very specialized consultant service into a more mainstream process, often blended with services like planning, master planning and concept design. Thus the discipline of programming has become blurred.

Perhaps a step back in recent history would be useful. Two important books were published forty years ago, Problem Seeking, by CRS and Emerging Techniques 2: Architectural Programming, published by the AIA. Both books presented the emerging practice and techniques which systematically defined quantative and qualitative facility needs. It was a predesign process and was viewed as specialty practice. In Problem Seeking, the classic quote and discipline separation was stated as "Programming is problem seeing, design is problem solving." As conceived and practiced, the programming research team was distinct from the design team and the program document was a thorough analysis and documentation of facility needs. It could stand alone as both a statement of requirements and as an evaluation tool for any design response to facility needs. A quote from the AIA Architects Guide to Facility Programming underscores the research perspective.

"It (the program) lays the foundation of information based on empirical evidence rather than assumption that helps the designer respond effectively and creatively to client requirements and facility parameters and constraints."

"Programming is an information-processing process. It involves a disciplined methodology of data collection, analysis, organization, communication and evaluation through which all human, physical and external influences on a facility's design may be explored."

The opportunity then is to reassess the methods, tools and techniques currently used to program within our profession, practices and building typologies. Considerable effort has been invested in developing templates and formats for quantative program/space needs and related programs. However a bigger opportunity still exists in regard to a wide variety of methods available to conduct primary research/facility program requirements. In Robert and Barbara Sommer's book, A Practical Guide to Behavioral Research, Tools and Techniques, they define the full array of methods appropriate for programming as research. Four basic techniques are defined: observation, experiment, questionnaire, and interview. When thought about specifically as programming, these techniques are most realistically practiced as a multi-method approach, combining observations, interviews and questionnaires, as well as case studies. The following outlines the techniques as both definition and reminder:

- Observation: includes casual observation, systematic observation, video recording, photographic recording, and behavioral mapping and trace measures.

- Interview: includes unstructured interviews, structured interviews, semi structured interviews, telephone interviews and focus groups.

- Questionnaire: includes open end and closed questions, ranking versus rating questions, matrix questions, group or individual survey, mail survey and internet survey.

I believe we should take Avigail Sach's advice to heart. We should learn from the early CRS "research attitude", look to the roots of architectural programming as a discipline, and as John Zeisel does, define programming as primary research.

Labels: design, history, programming, research

This I Too Believe

Somehow I'm still in a reflective mood and have recently been looking at an out-of-print book about

Bill Caudill. As one of the founders of Caudill Rowlett and Scott, (CRS), Bill was a driving force and role model as an architect, educator, researcher and author. The book,

The TIBs of Bill Caudill, collects a small subset of writings that he prepared over twenty years, from 1964 until his death in 1983. The abbreviation stands for 'This I Believe' and the TIBs were distributed by memo to CRS leaders and displayed on office bulletin boards. The introduction to the book by then CRS Chairman of the Board, Tom Bullock, directly asks:

Why did he write them?

'Good question,' he once replied. 'To pinpoint things we really believe in? To encourage and express the openness that characterizes our company? To communicate thoughts on current issues? To produce responses? To carry on a continuous writing of our history? Paper therapy? Perhaps all of these.'

Probably the best answer is that he wanted to improve his thinking by expressing himself regularly in clear, simple thoughts. 'Most of us need to write/think,' he said.

The CRS archives at Texas A&M contain over 4,000 TIBs and, for those who may be interested, you can sign up at the site for a service that will email you one TIB each week. Me, I still like to open the book and flip through it, reading and thinking about his ideas and their relevancy to today. I think what Bill was doing with his TIBs was a sort of analog blogging. Most of the memos, if produced today, could be blog posts and some of the more concise thoughts would fit perfectly into the limited number of characters for a tweet. So to bring his TIBs into today's world so others can also discover or rediscover a designer, practitioner, researcher and educator who believed that learning never stops, every now and then I'm going to add my thoughts and post or tweet a flashback quote from Bill Caudill. Enjoy and learn.

TIB

Education -- NEVER COMPLETE

26 December 67 WWC

ARCHITECTURAL EDUCATION IS NEVER COMPLETE.

It is adquate when one has 1) developed sufficient skills, 2) absorbed every possible detail of knowledge, and 3) accumulated enough experience to ensure reasonable solutions to problems encountered by new work. Without all three -- skills, knowledge, and experience -- the architect is hard pressed to operate with any degree of competency.

If he hopes for precision in architectural practice, let's say the design approach, he must face the realization that education must continue at a greater pace than he experienced at the university.

This I believe.

Labels: architecture, history, thinking, writing

Fortieth Anniversaries

1969, the end of the turbulent 60's, was a year of national, international and personal milestones. Now forty years later, I find myself reflecting on the events which shaped my generation and influenced my personal and professional path.

The first of the forty-year anniversaries was our February wedding and honeymoon in our semi-complete ski house in Vermont. Getting snowed in so completely we were unable to get to the ski slopes, we spent the first day as newlyweds tiling the downstairs bathroom. That day was not only the start of many future housing renovations and construction projects, but of never missing an opportunity for accomplishment, regardless of the situation. Back in Somerville, we moved into our first apartment, painted some super graphics on walls and a radiator, got some furniture and started our life together. That spring I applied to the new graduate program in architecture at the State University of New York at Buffalo and we got ready to set off on another new adventure.

The summer of 1969 marked three more fortieth anniversaries: the New York City Stonewall riots in June, Apollo 11 in July and the Woodstock Festival in August. All were events of our time, marking the start of the gay rights movement, the completion of Kennedy's challenge to put a man on the moon, and a musical high point of the peace and love era. Along with millions of other people, we watched the Apollo mission on television, and we did drive from Boston to New York State in August - just not to Woodstock. Our trip was to Buffalo, New York for the start of graduate school in the very first year of the architectural program at SUNY Buffalo. What an adventure it was: a new city, a new professional direction and the purchase of our first home together. Very exciting times.

As I think back to the start of the

graduate program, I'm reminded of people, process and purpose. Much humbler, but not unlike the goal of the space program to put a person on the moon, the school's innovative, even radical, purpose was to broaden the context of design and architecture by putting man and environmental considerations into the practice of architecture. The history of the school acknowledges John Eberhard as the visionary first dean of the School of Architecture and Planning and provides a thumbnail sketch of how it began. However the following quote forty years later by John in his most recent book,

Brain Landscape,

the Coexistence of Neuroscience and Architecture, puts the origin of the school into his own words.

An opportunity I couldn't resist presented itself when Martin Meyerson, president of the State University of New York at Buffalo (SUNY-Buffalo), invited me to start a new school of architecture at his university. He arranged for my new school to report to three provosts: Engineering, Fine arts, and Social Science. I decided to have this school focus on an inter-disclipinary graduate program, which would have as its purpose educating a new generation of architects who could organize and manage research projects--as contrasted to designing buildings. We formed a nonprofit organization outside the university called BOSTI--the Buffalo OSTI related to my friend Don Schon's research organization in Boston. During the next 5 years, our team of graduate students participated in more than 50 projects--all of which were funded through BOSTI by outside organizations.

The first person John asked to join his mission to build a new school was the late

Mike Brill. Mike and John had previously collaborated at the National Bureau of Standards Institute for Applied Technology, using design-research teams that applied systematic analysis to problems in the built environment - a systems oriented, people committed social vision. Mike was the first chair of the graduate school and developed the research/teaching arm called BOSTI, Buffalo Organization for Social and Technological Innovation. The first class of twenty graduate students was a mature group from a variety of undergraduate majors, setting up the multi-disciplinary approach. All had altruistic, knowedgeable, energetic restlessness with the status quo. Banding together with purpose, they were rebels with a cause.

Those first months of a teach/learn experience in a program without a traditionally structured curriculum explored the roots of the educational model. A number of components of the vision and process were tested live on our experimental class, including: the multi-disciplinary approach to environmental design, projects as educational vehicles with real design-related problems and real clients, team learning in faculty-student teach-learn mode, research in action education funded through BOSTI, user-based, systems-oriented problem solving, and performance-based measurement of outcomes. The flavor and spirit was clearly activist and anti-establishment, particularly toward the architectural profession and schools which favored visual design education without social constructs. Assigned readings, such as Systems Approach by Churchman, General Systems Theory by von Bertalanffy, Structure of Scientific Revolution by Kuhn, Personal Space by Sommers and Hidden Dimension by Hall, supported systems thinking about social issues. Kuhn's book introduced the word 'paradigm' and John viewed this program as the new paradigm.

Forty years later, I can still see the space where we worked, its walls covered with diagrams, images, charts, and goal evaluation matrices from our projects, research or class assignments, yet I can also see how much of what was set out back then as a way to change architectural schools and practice, still remains incomplete today. Recently I took on a new role in our organization as Director of Research with the goal of completing the research-based practice loop started in Buffalo. While contributions from social science have continued to provide much more useful research about the design and use of the built environment, currently called evidence based design, the bridge between systems-based research and the mainstream practice world is still incomplete. My work started forty years ago with that drive to Buffalo, and the journey continues.

Labels: architecture, history, research